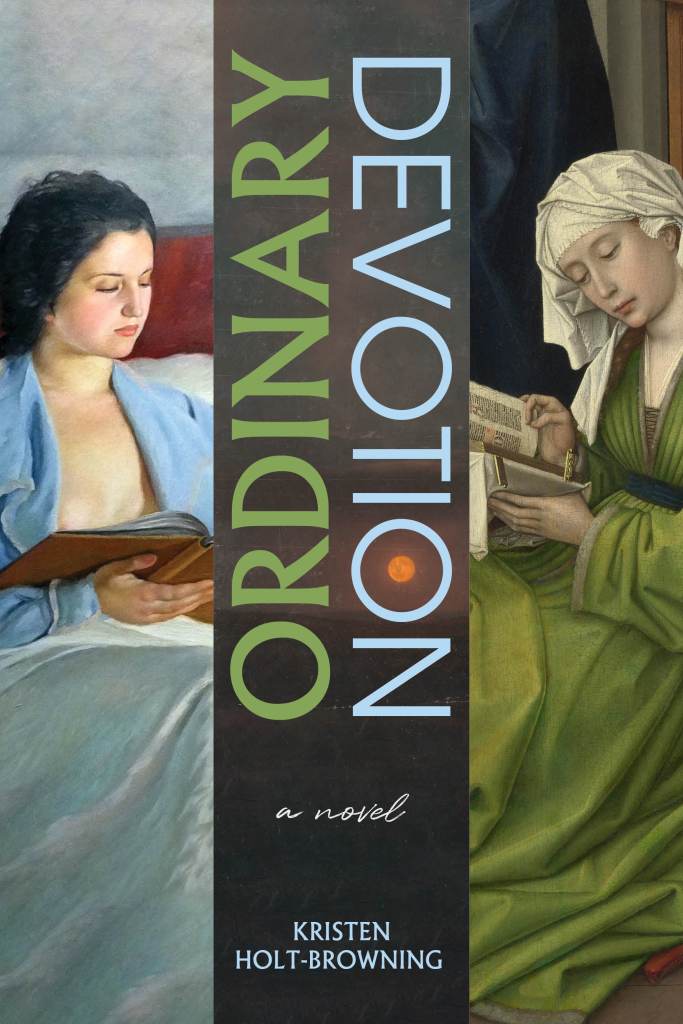

Kristen Holt-Browning’s Ordinary Devotion

Fans of historical fiction, especially the well-written kind that trace parallel

lives separated by time, will delight in Kristen Holt-Browning’s recently published novel, Ordinary Devotion. Through lyrical prose, a nimbly constructed and fast-moving plot, detailed descriptions of life in two centuries, and scenes of high spiritual drama, this thoughtful book explores timeless themes in women’s lives that are especially timely now.

Chief among them are the physical dangers and emotional challenges of women’s reproductive lives, including those of pregnancy, miscarriage, and death in childbirth. Other related themes include the juxtaposition of soul and body (especially the female body when considered the gateway to sin), confinement and mobility, and faith and autonomy: not to mention the costs of sex and freedom of body and mind.

The story is told in alternating chapters narrated by two female protagonists. In the first, Elinor, a twelve-year-old girl in 14th century England, describes her horror and spiritual trepidations as she is closed in a small, dark cell with only a peephole for light and a companion she can barely see. She’s on her first day on her first job as assistant to an anchoress—a woman who volunteers for a life of prayer and mortification of the body, in a sealed room attached to a church or monastery. Lady Adela has chosen her vocation, one which offered medieval women a rare path toward autonomy and respect free of sexual duties, but Elinor, a bright child who loves nature, air and light, is there at the choice of her father, who is honoring the wish of her mother, recently dead from having given birth.

The second chapter introduces Liz Pace, a 35-year-old, pregnant, married, underpaid adjunct professor of medieval studies at a New York State college in 2017. Her specialty is purgatory, but distracted in a bookstore by the work of another more successful female academic, she becomes fascinated by the idea of anchoresses and embarks on a new scholarly path that will eventually lead her as close to Elinor as possible. At this point, both she and Elinor are at the bottom of their respective employment ladders. Thanks to their innate resilience, sound female mentorship, and some support from better-paid men, each grows in her job. Adela teaches Elinor to read and pray the hours along with the monks while Liz’s miscarriage brings not only grief but freedom to pursue her research. Along the way, both become women of greater knowledge and compassion.

While still in the bookstore, Liz, who’d like nothing more than to talk with someone from the past, imagines explaining electricity, coffee, and the mass-production of books to a medieval monk who has somehow managed to join her. This fantasy nicely sets up the contrast between historical periods that continues throughout the book and her deepest motivation as a scholar.

The device of using two narratives allows Liz to provide most of the historical information that underpins the novel, as well as her own experiences and feelings. We learn through her that when monks bricked over the door to an anchorage like Adela’s, they recited the prayer for the dead. And that only a small opening was left through which to pass food and chamber pots and allow the anchoress to talk to visitors. These were often pregnant woman in need of prayers and sometimes, more practical assistance. Through Elinor, and Adela, whose past holds a significant secret, we experience how living in an anchorage felt which is what Liz really wants to know.

In her own life, Liz comes to feel that pregnancy and simply having a woman’s body is a form of purgatory, an enclosed in-between, liminal state that can lead to experiences of either heaven or hell. In the 14th century, Adela states that the true enclosure is not the cell but her body while Elinor, even after the pain of menstruation makes her a woman, holds to her sense that her body like the rest of nature is meant to be a source of joy.

Throughout, Holt-Browning’s descriptions, whether of the most transcendent states or the grimiest, are physically precise, perhaps because the author is a poet as well as a novelist. At one point, the singing of monks in their adjacent church sweetly penetrates Elinor’s anxious dream. At another, Elinor describes the cell as only a dark stone place in which there are two dirty bodies. Ordinary Devotion is a work of passionate clarity, in which matters of the soul are beautifully shown to be inextricable from those of the body.

/////

Kristen Holt-Browning is the author of the novel Ordinary Devotion (Monkfish Books, 2024) and the poetry chapbook The Only Animal Awake in the House (Moonstone Press, 2022). Her work has appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Hunger Mountain, The Westchester Review, and several other publications. She lives in Beacon, NY. Learn more at http://www.kristenholt-browning.com, or follow her on Instagram (@theholtbrowning).

Reviewer Catherine Gonick is a contributor to Lightwood. Read more of her work by scrolling to the Search Button, insert her name and click.