When I was a child, I attended synagogue services with my father on Saturday mornings. I don’t think he was religious at all, but he liked the ritual of the service and the familiarity of the congregation. He would greet everyone and chat, even though he generally wasn’t a particularly sociable person. When my parents got engaged my grandmother advised my mother that my father had no capacity at all for small talk and that described his conversational spectrum pretty accurately, but there were only about 50,000 Jews in Johannesburg in those days, so most people knew most people, and in our synagogue he assuredly knew everyone. On Shabbat, when the congregation was composed only of the most stalwart regulars, my father didn’t have to say much for everyone to feel that enough had been said.

We belonged to the Great Synagogue in Wolmarans Street, a large red brick structure modeled on the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, with a high domed ceiling supported by pendentives. One entered through a grand lobby paved with black and white marble tiles where the gentlemen would wait for the ladies to descend the magnificent double staircase after the services. On the High Holy Days, when the sanctuary was packed and everyone was dressed in their finest, there was a sumptuous parade of mink coats down the stairs even when the weather was quite warm because no lady of that generation wanted to be identified as minkless, whatever the season. In spite of the complexity of the structure it was surprisingly plain inside, because when it was built there wasn’t enough money for any elaborate finishes. My grandfather had been one of the founder members in 1914. This was only 20 years after he had arrived in South Africa from Lithuania at the age of 18 and only 28 years after the founding of Johannesburg as a consequence of the discovery of the gold reef a couple of years earlier. But for poor kids from the shtetl, fleeing the pogroms, there was so much opportunity to make money that although they were still quite young, they could afford to build a very nice synagogue indeed, notwithstanding the plain interior.

Our family seats were in the front two rows right in the center which is one of the perks of being descended from one of the founders. We could therefore see everyone as we entered and of course they could see us walking down to our seats, and I was always a bit put off by the grim-faced old men who scowled at me as I walked down the aisle because for children grim-faced old men are not only enigmatic but discomfiting. Only as I grew older did I get some insight into these people— they also had come from the shtetl, but they belonged to the group that hadn’t enjoyed the success of people like my grandfather. They were tailors and cobblers and tobacconists who lived in dark little flats in the built-up areas not far from the synagogue, so a well-dressed little boy, who clearly wasn’t going to have the challenges they had had in life, was a reasonable object of some resentment.

After the service my father and I would take the relatively short walk over to Jeppe Street, in downtown Johannesburg, to the Nedbank Building. Other than the theatres and cinemas and a few assorted eateries everything in Johannesburg closed from noon on Saturday until Monday morning, so there weren’t many people around and we walked quickly. Around Joubert Park, which abutted Wolmarans Street, we would see crowds of black workers waiting to board the PUTCO buses that would take them home to Soweto, or whichever township they lived in. One could never get close enough to them to see that they were also individuals, each one as unique as any of us is, so what I saw was a mass of black people with nothing to distinguish one from another. The dehumanization of the black population was, of course, the most fundamental tenet of apartheid and we glanced dispassionately at the crowd from a distance as we strode by.

During World War II, a friend of my father in the armed services had been badly injured in North Africa, and he had been taken to the military hospital in Pretoria. The friend’s parents didn’t own a car so my father would drive them over to visit him. In those days one took the old Pretoria Road from Johannesburg, which was a two-lane affair on which speed was not a possibility, so it was quite a long drive. My father’s friend did not survive but my father remained friends with his parents, Jan and Olive Bragaar, for the rest of their lives. Olive Bragaar was an Afrikaans woman who was a great talker though not necessarily an interesting one, and the snippets I heard here and there seemed primarily about her daughters and grandchildren. But Jan Bragaar, who was Dutch, seemed always very good humored especially with my dad. Clearly, they had a special bond. Mr. Bragaar was then the superintendent of the Nedbank Building, and it was the Bragaars that we were visiting.

When my father and I reached Jeppe Street and the Nedbank Building in that long-vanished time we would ring the bell downstairs and Mr. Bragaar would come down to collect us in the manually operated freight elevator to take us up to their apartment, which was essentially a little house on the roof of the building. It was quite modest, but it was neat and comfortable, and it had a covered verandah, which was very practicable in that climate. There my dad and Mr. Bragaar would sit at a little table and play chess in the shade while Mrs. Bragaar served them tea. Because it occupied such a small part of the total roof area their house looked out on a large expanse of silver painted built-up tar roofing on which Mrs. Bragaar had created an amazing garden of flowering shrubs in various pots and jars, all thriving in the hot subtropical climate. But although I would wander between the pots to admire the plants, that was not my principal interest out there. The parapet wall around the roof was quite high, and certainly taller than I was at that age. However, Mr. Bragaar had placed piles of bricks at various points around the periphery to support heavy wooden planks, and what I liked most was to climb up on to one of the planks to look out at length over the wall at the still and silent expanse of Johannesburg shimmering in the Saturday afternoon sun.

/////

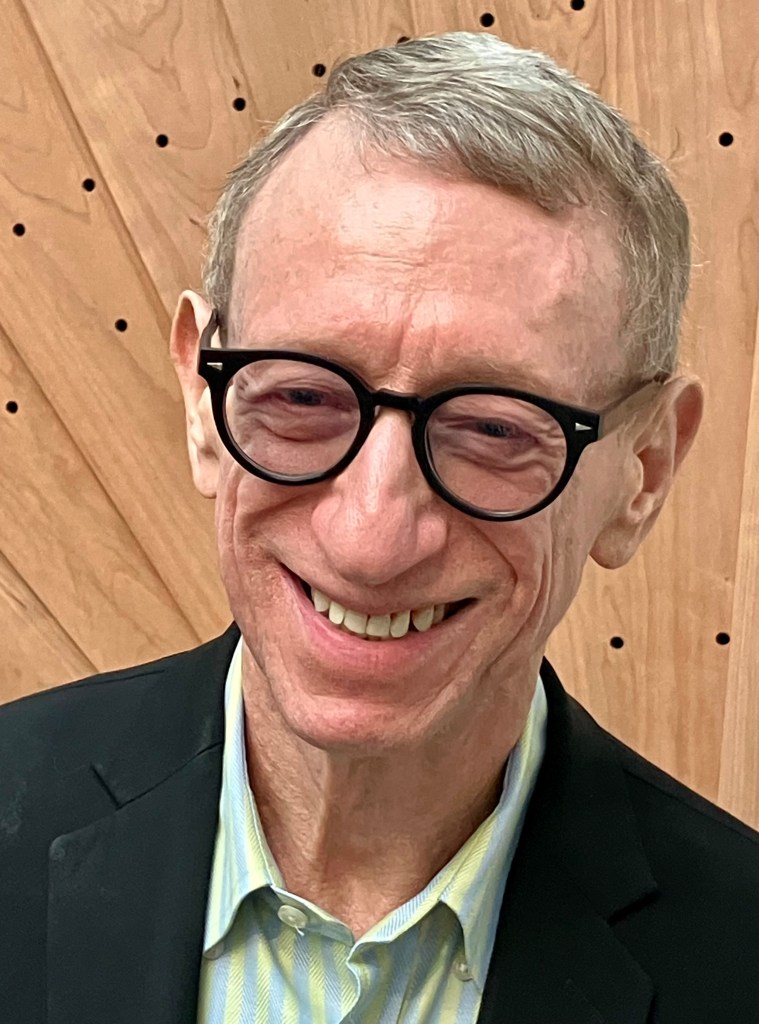

Read Alan Sive’s memoir/essay, “Moving On: The End of the AIDS Crisis in New York” here on Lightwood. It is part of a book-length work about his years in New York from the 1980s to the 2010s. Scroll to Lightwood’s Search Link and insert his name.

Author Alan Sive grew up in South Africa under apartheid, which, aside from the political and cultural isolation, was a perilous environment for a gay teenager. He then moved to England and studied architecture at the Architectural Association School in London, but finding little work when he graduated, he moved to New York. He attended Columbia University Business School in the hope that an MBA would improve the chances of finding success in the US. This proved elusive. “There was malice involved, and bad timing, but primarily there was the AIDS crisis. Still, I am here. I have survived. Now there seems nothing else to do but to write.”